Understanding the economic and social implications of climate change at the local level is a critical area of research when it comes to the tourism sector, as travelers often base their choice of destination on factors such as weather. A new CMCC study finds that, in the absence of climate policy, the Italian tourism sector will face dire consequences, with cities such as Rome facing a potential loss of hundreds of millions of euros per year in 2050.

The tourism sector is a source of sustenance for local communities, a driver of fiscal revenues and a way to connect local sites to international guests. In Italy its has an increasingly big impact on the national economy, with recent studies indicating that it accounts for up to 13% of the national GDP, generating 25% of new jobs and Italian cities experiencing a +15% growth in overnight stays in 2023.

However, tourism is also extremely vulnerable to climate factors such as variations in weather patterns. A new CMCC study looks at how tourism in italian cities will be impacted under different climate change scenarios by looking at the relationship between tourism supply at the Italian Municipal level and climate quality, proxied by the “Holiday Climate Index” from Copernicus, which is an indicator of climate quality for tourism activities.

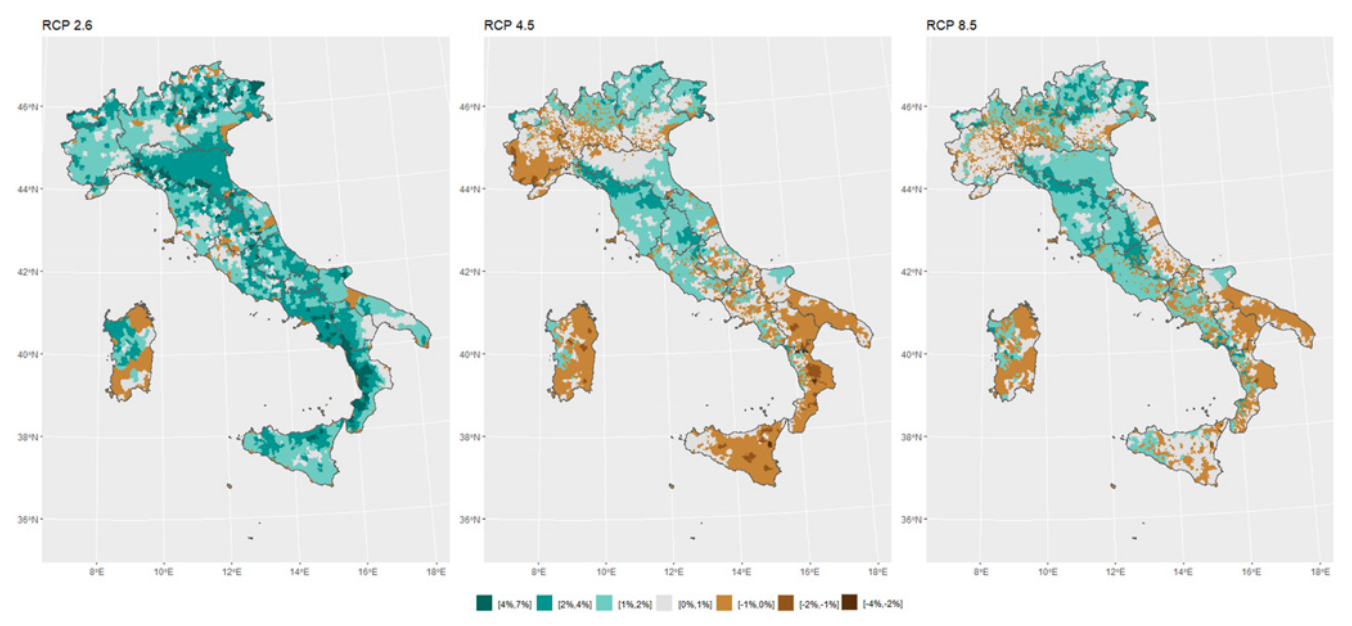

The study looks at tourism supply at the municipal level in Italy in terms of the number of beds per kilometer squared under three different warming scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathway 2.6, 4.5 and 8.5) for 2050, revealing that areas such as the Venetian Lagoon, Milan and Sardinia will suffer systematic losses even in optimistic scenarios such as the RCP2.6.

“In the study we found that, according to the location, even just one percentage point of loss in quality due to climate change may lead to a forced adjustment in supply,” says lead author and CMCC researcher Matteo Mazzarano. “In Rome, this would be equivalent to a loss of hundreds of millions of euros per year in 2050.”

This highlights how climate change is a source of systemic risk for the tourism sector, and also reveals how instances of inequality, such as Italy’s north south divide, would be exacerbated as northern localities are, on average, relatively less damaged in tourism supply by climate compared to southern ones. However, there are notable exceptions to this trend, namely the planes of the Po being severely affected in case of a delayed global reduction effort (RCP4.5) and the western coast of Calabria possibly gaining from any increase in GHG.

“Overall our model shows that areas that may experience any positive change from climate anomalies are few and far between,” says Mazzarano, who also warns that even if some areas do see minor positive adjustments due to a more favorable climate, this would not compensate other climate related losses that would impact the rest of the economy.

The figure shows possible losses or gains in tourism under different RCP scenarios. Source: Mazzarano et al. 2024

Furthermore, the study uses a detailed econometric model that could also be reproduced for other areas, from a European to a global level, as the approach effectively implements geographical characteristics and proximity to infrastructure to control each municipality’s isolation and peculiarities.

“This study is part of a larger project in which we look at the economic and social implications of climate change at the local level so that we can create scenarios that are useful to policymakers that, among other things, rely on tourism as a source of tax revenue,” says Mazzarano.

For more information:

Mazzarano, M., Galluccio, G., & Borghesi, S. (2024). Italian urban tourism predictions using the holiday Climate Index. Tourism Economics, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166241277858